In the last week many of my academic friends who don’t study news have gotten a lot more interested in “fake news” as a potential social problem. First there was the Buzzfeed story claiming that the top 20 fake news stories during the last few months of the election got more Facebook engagement that the top 20 “real stories.” (I’ll talk more about that study itself separately.) Then there was the NPR story on a psychology experiment showing that students couldn’t adequately separate more and less credible sources of information. Since most people don’t have direct experience teaching about news media, let alone this new issue of fake news, there’s a lot of things I could share. It’s hard to know where to start. I’m going to write a few separate posts.

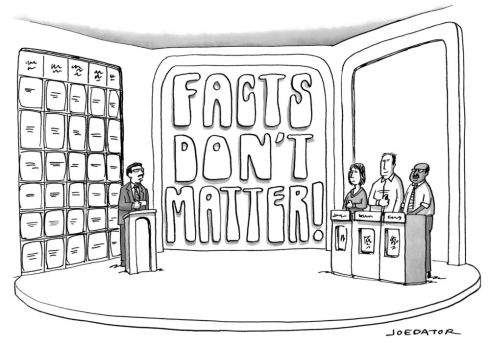

Let’s start with the most basic idea of how to stop fake news. Why not just hand students a list of websites and say “these websites are fake!” Google and Facebook blacklisted a set of websites after the election, trying to keep fake news from benefitting from their advertising networks. Giving people a list of websites makes me think of giving someone a fish versus teaching someone how to fish. Is fake political news written by teenagers in Macedonia more important than politicians selectively giving information to manipulate prestigious reporters? What about the growth in political memes that have no facts, only feelings? I think this New Yorker cartoon sums it up well:

Caption: “I’m sorry, Jeannie, your answer was correct, but Kevin shouted his incorrect answer over yours, so he gets the points.”

I don’t know if the cartoonist is aware of the irony here. There’s a big banner saying “FACTS DON’T MATTER.” There’s a caption that captures part of the reason progressives resent Donald Trump and his electoral victory. But there are no actual facts in this political cartoon. We don’t know what Jeannie or Kevin said so we can judge the answers for ourselves. Of course, giving facts is not what political cartoons do. They try to present clever mockery. I understand why the cartoon feels true. But the key to distinguishing fake news and other kinds of emotional manipulation is being able to separate literal fact from arguments that feel true or symbolize truth without containing verifiable facts.

Just to give a preview of where I’m going, every style of telling stories has strengths and weaknesses. For my final in Sociology of Mass Communication a year ago I asked students how they would write about the Trump campaign. Why did they choose that style? What are the strengths and weaknesses of that approach? If a student couldn’t talk about the negative ramifications of their decision, they couldn’t get an A. I knew that students could think about the cons of each approach, they could walk out of my class knowing how people may try to use that style of story telling to manipulate them. Sometimes it’s politicians using the media. That’s been one of the main themes of this blog in the past. But since people are mainly worried about fake news today, I’m going to focus more on media producers trying to manipulate our emotions.

I didn’t teach about “fake news” per se when I taught sociology of mass communication a year ago. I’d only change one thing if I taught again this Winter or Spring, and it’s something much broader than fake vs. real news. Fake news is just one kind of manipulation. The New Yorker cartoon is another. Donald Trump dragging out the hot takes over Mike Pence getting booed while watching the play Hamilton is a third kind of manipulation. I’m less concerned about the differences between flat-out lies, tactical half-truths and people relying on emotional arguments because they don’t have facts or evidence to back up their claims. Each form of manipulation can be resisted by asking the same set of questions instead of taking content at face value.

1) How much does the article rely on factual claims or evidence? Some articles are entirely descriptive, trying to relay a set of facts for an audience who didn’t directly see what happened. Other articles rely heavily on moral claims and interpretation rather than empirical evidence. That’s a different type of argument and we’ll get to it in a bit. Traditional interview-based journalism offers quotes as a kind of evidence. Direct evidence from documents is rare.

2) If someone relies on factual claims, where does the evidence come from? Can you clearly trace how evidence traveled from the original source to intermediaries to your brain? For example, reporters interview people and quote them. We don’t know what the reporter decided to quote and what was left out. But we can be fairly certain that the person being quoted said those literal words. Then we can evaluate the reputation of the person being quoted. We can also evaluate the reporter’s reputation. If we can’t clearly trace the flow of information from one person to the next, they may want to hide something. Whistleblowers need anonymity for protection. However, a wide range of political operatives seek anonymity to promote half-truths and misinformation.

3) What emotions is someone trying to convey? Are they trying to make you feel a certain way about things? Some writers and meme creators’ goal is to convey a certain set of feelings. Think of the New Yorker cartoon: it wants to convey outrage. Most newspaper and network TV reporters work very hard not to convey any of their own emotions about the stories they are reporting on. This kind of stoic emotional restraint is pretty rare in other kinds of storytelling. My goal is make sure we all pause and consciously understand where a writer is coming from and what they want us to feel. I don’t want to get my emotions pushed around by anybody, even people I tend to agree with. Any time someone is giving us a set of feelings that we want to believe, we are at risk of not checking their facts and evidence as closely as we should.

4) How honest and up front is the writer about why they are doing what they are doing? I actually haven’t taught this before, but I think it’s an important follow-up to question 3. Every argument has assumptions. If someone is making an argument, how much are they willing to clearly state “here are my goals and my assumptions.” When someone is giving an interpretation of evidence, do they explain why they gave this interpretation? Do they acknowledge other potential explanations and make a case for why their interpretation is better? If someone can’t acknowledge that other interpretations exist, it’s probably because they can’t make a good case for why their interpretation is the best.

My own sense from spending my entire adult life working in or studying journalism is that it’s hard for a writer to excel at giving both factual evidence and feelings. I think it’s particularly hard to combine the two when writing about politics, since the main feelings people convey are moral outrage and judgment. It’s much easier for me to try and combine facts and feelings when recapping a baseball game than in writing this post. That’s why there are tradeoffs. No writer can be consistently good at everything. No one is perfect.

When I teach about journalism, my main goal is to get students to acknowledge these tradeoffs, then ground them in specific examples. Elite media organizations that have access and avoid reporters’ personal judgments tend to defer to sources in order to protect access. When Trump lied on Twitter about the popular vote, many leading news organizations copied his claim in the headline without any critical skepticism. Large news organizations tend to fear an inability to prove an elite source is lying more than they fear publishing an elite’s statement that is probably false. Nixon campaign aides first took advantage of this in 1968 (see Crause’s Boys on the Bus), and it’s been a staple in political operatives’ playbook ever since.

Writers who emphasize moralistic takes and emotion have more incentive to hide, selectively misinterpret or fabricate factual evidence. Someone who really wants to convince me that Trump voters are all racist isn’t all that likely to bring up other reasons why they support Trump. On the other hand, Trump voters who are not explicit supporters of the KKK are trying to emphasize all the non-racial reasons why someone would vote for Trump. Three weeks after the election and I still see both messages from friends, like it was the day after the election. That’s why things like the New Yorker cartoon stick out to me. They encapsulate outrage and victimization, but are not going to persuade anyone who doesn’t already have those feelings deep in their heart before reading the cartoon.

Being self-conscious about what we want from news is hard. I think it has always been hard. We don’t want to acknowledge that every genre of media is imperfect. People who want all-facts news may not want to acknowledge how reporters can be manipulated by powerful sources. People who want a certain set of emotions, moral stance or political ideology may not want to acknowledge there are times they put feelings before facts. Trump exploited this his entire campaign, skewing this election almost entirely towards emotion. Remember that Democrats’ main campaign theme was that Trump was emotionally unstable and personally unqualified for office. We took the bait instead of focusing on a positive message. It’s easy to see something on social media, get agitated, and react right away. This is a more pervasive and bipartisan problem than “fake news.” For another example of what makes this so hard, let’s take the following passage from the end of an article Dara Lind wrote for Vox:

Journalists have long been sensitive to the prevalence of misogyny on social media. In 2016, they’ve become alarmed by anti-Semitism on social media as well. Journalists know and work among women; they know and work among Jews.

Many of them don’t know and work among many people of color. The amount of attention paid to racism on social media (or in real life) among journalists is, accordingly, often disproportionately small — or delayed.

Let’s think about how to factually evaluate the claim that journalists pay more attention to misogyny and anti-Semitism than racism. We could try to construct a database with a list of misogynist incidents, religious bigotry and racism, and then construct a second list of writers and what they wrote about. How often did a particular group of writers tackle a particular topic? This is incredibly difficult, painstaking work. I spent years working on a project like this dealing with media and blog posts from the 2008 election as part of my dissertation. In the end, I could produce criteria for defining statements on race, gender, religion and a large number of other topics. I could produce data on how much a particular set of news organizations preferred or dispreferred phrases on each topic, relative to any other topic.

Even if I provide facts, there is no factual basis for saying whether enough attention is being paid to racism or misogyny or any other issue. The current level of attention is a fact. The ideal level of attention is a feeling. It’s a moral stance. I chose this passage from Lind’s somewhat unrelated article because it does a great job of showing how 100% fact based story telling only goes so far. A description of how much attention is currently being paid to race with no moral claim about how much attention should be paid to race will be unsatisfying for many audiences. Trust me, I have the negative reviews to prove it. On the other hand, moralistic claims that lack evidence are unsatisfying for a different audience. Lind claimed that journalists pay a disproportionately small amount of attention to racism. The rest of the article doesn’t give any additional evidence to support this claim since it is largely focused elsewhere. Unfortunately, that means I have no idea if Lind is trying to manipulate me or not.

If you want to teach critical thinking about media content and not just give students a list of fake news sites, you have to empower students to offer different moral priorities than you. I know some students in my last class liked outrage news a lot more than I did. I assume some of my readers will like it more than I do. That’s fine. My students also liked Buzzfeed’s day-to-day content a lot more than I did, while I wrote lectures while listening to three hours of college football podcasts. I made a point to illustrate a few of my eccentric non-political preferences to set a tone that I didn’t expect them to copy my political, moral preferences either. My goal is to help people make better informed choices about what media we read so we can be aware of what we are not getting. I want us to be able to protect ourselves from all different kinds of deception in the news – particularly from writers we tend to trust the most.

November 30th, 2016 at 11:38 am

[…] think the key is to look for potentially disconfirming evidence. I wrote about this at more length yesterday, but here’s the short version. As a person sitting in my apartment writing a blog, I […]

November 30th, 2016 at 8:57 pm

I’m not so sure about emotions free descriptive reporting.

There’s a rhetorical ploy journalists and social scientists use a lot, to maintain face (their performance of stoic dispassion), whilst delivering a motivated conclusion. To wit, they become experts at suggestion.

So, for any statement, a listener confronts some weighted decision tree, right? All statements have myriad meanings, in themselves. Then each one of those meanings implies, again, another distribution of more or less common next things that might get said. This is why people can finish each other’s sentences when they’ve known each other for a while, and presumably is where linguistic cliches and phrases come from, no?

So a reporter or social scientist will say something that appears, superficially, to be matter-of-fact.

But indeed if I write an article reporting a litany of low ranking human development measures from America, pause with a paragraph break, and end it with a one sentence paragraph that says, “President Elect Trump said at a press conference yesterday that America is the greatest country in the world,” I’m not just reporting facts. I’m suggesting that Mr. Trump is either ignorant, lying, or focused on measures of American well being other than those I’ve cited.

I don’t mean to pitch that I’m uniquely aware or intelligent, but I noticed this about journalistic writing well before I had any academic training. It’s not some great mystery to most folks that a lot of journalism and public discourse generally is a large game. Maybe this helps us understand why people could really just give a fuck anymore that mainstream journalists and other anointed intellectuals no longer get to make the rules for that game.

I’m much more worried about being manipulated by people who appear to be dispassionate arbiters of facts than I am by people who’s desires and emotions are conveyed in a straightforward manner.

November 30th, 2016 at 10:05 pm

When I taught about news and politics in my Sociology of Emotions a year and a half ago, I started by playing this clip of Walter Cronkite announcing the death of JFK: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6PXORQE5-CY

I did regular short writing exercises as a way of taking attendance. So I asked students “If someone handed you a note saying the president had just been killed, and you had to go on live television, how would you tell the story? Would you behave differently than Cronkite?” I intentionally chose a case where trying to be stoic and giving off relatively few emotions would seem impossible, but Cronkite is giving that performance. (I was going to write that up separately.)

I know there are certainly people who prefer the “here is my stance” form of writing. In my experience people who feel very strongly about doing their own advocacy feel more comfortable around others who take the same approach in writing. Empiricists are more comfortable around other empiricists. Like I emphasized, every form of writing about politics has drawbacks. Copy/pasting Trump (or Obama, Bush, any powerful figure) is the drawback of today’s legacy media organizations. It’s been the drawback for as long as they have gotten access. As I’ve mentioned before, the entire premise of my dissertation was that politicians can predict and take advantage of legacy media organizations. In this post I focused more on the drawbacks of partisan media, because they tie in to the current debate over fake news.