Last week I walked past the single worst Black Friday ad I ever saw. A local clothing store advertised “openning” 10-6 on Thanksgiving. Yikes! Was this the worst Black Friday behavior I have ever seen in my neighborhood? It’s close, but I saw worse at the local Best buy a few years ago. While I was shopping for a laptop bag, a woman was complaining to customer service that she was locked out of her accounts. Apparently someone texted this woman claiming that she had won an award. She just needed to send her banking information to get paid. Of course, it’s a scam. I turned around to look at the low level best Buy employee and saw the quick look of terror on his face. How does he explain that this potential customer just got scammed and there’s nothing he can do to help? How can he be sympathetic to this confused woman walking in to Best Buy with her child instead of wanting to scold her for falling for such an obvious deception?

If you’re an old enough Internet user, you probably remember scams involving “Nigerian princes.” In case you forgot, this was a scam where someone sent bulk spam email claiming to be a Nigerian prince who has to move money offshore due to political unrest. If you give your bank account info, they would wire $10,000 to your account. Most people realized this was too good to be true, even before the scam became publicized and tech firms dedicated resources to blocking these spam e-mails. However, there were some people who desperately wanted to believe there was a Nigerian prince who would make them rich. Selfishness and laziness beat suspicion and careful research. The selfish and lazy might be pretty easy to exploit.

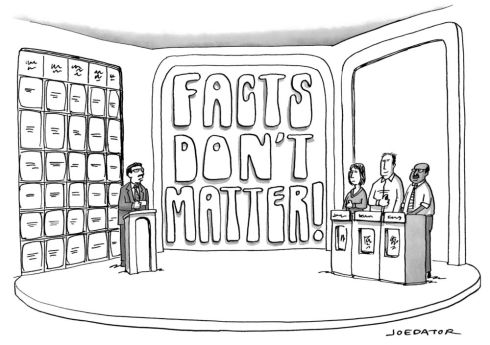

If you follow tech news over the last week, you saw headlines that the top 20 most shared stories on Facebook had more fake news stories than real ones. Google and Facebook both blocked fake news sites from their advertising sales networks this week – now that the US Presidential election is over. Facebook has always had an unusual set of “community standards” for regulating content. Visual depictions of violence and sexuality are generally banned. The company frequently claims it has tweaked its “News Feed” algorithm to show “higher quality content” as opposed to clickbait. However, Facebook has always strenuously objected to the idea that it is a media company with a profound influence on journalism. Here’s Mark Zuckerberg, trying to answer questions about whether his company helped Donald Trump win the 2016 election:

“Personally I think the idea that fake news on Facebook, which is a very small amount of the content, influenced the election in any way — I think is a pretty crazy idea. Voters make decisions based on their lived experience.”

I’m not sure anyone really believes this, even Zuckerberg. Facebook acted against fake news sites four days after Zuckerberg’s quote (and after Google’s ban). It’s a field day for people who want to blame Facebook’s lack of transparency – or social media more broadly – for Americans’ declining interest in facts and evidence. As much as people have a right to be frustrated that Facebook didn’t do anything about fake news until after the election, it’s not like Facebook was the birth of online scams. People have tried to use the Internet to try and exploit selfish and lazy users for decades. They used other technologies before the Internet. Instead of blaming Facebook, we should ask why would people want to spread misinformation with their friends and family?

My take here is probably different than most people because I actually covered a secession campaign. In 2002, the San Fernando Valley wanted to secede from the rest of Los Angeles. The secession movement started as part policy oriented and part symbolic. Every public school in Los Angeles County is in one school district. Valley voters wanted to break away from the unwieldy behemoth. They also believed their tax dollars were being used to subsidize the poorest neighborhoods of Los Angeles. On a symbolic level, Valley residents felt like they were taken for granted by a remote city hall. It wasn’t a rural / urban divide like presidential elections. If Valley voters formed their own city of Camelot, it would have been the seventh largest in the country! (Sidenote: Camelot won the vote for what to call the new city.)

By the time I started covering the story, Valley secession leaders had already conceded on their largest policy grievance. Camelot would still be part of the LA Unified School District. I talked to voters who said “what’s the point of seceding if we’re still tied to LAUSD?” Other reporters thought there was no way secessionists could get enough votes. They needed to run up enough votes from within the Valley to get a majority citywide. Secessionists didn’t fully want to campaign on keeping Valley tax revenue in the Valley either. The county ruled that Valley residents would have to financially compensate the rest of Los Angeles if secession passed, to make up for lost tax revenue.

With only a weak policy case, potholes became a major campaign issue! Some Valley residents saw every pothole as a reminder that their area didn’t get a “fair share” of city services. Mayor Hahn dispatched construction crews to smooth over problems, both literally and figuratively. (At this point I am obligated to say I don’t live in the Valley and my street gets enough flooding to become one lane only during moderate rain.) Valley secession leaders wanted voters to feel like City Hall was remote. They also reminded people that most local media organizations were located in the older area of the city and not the Valley, so they were biased against secession. The Los Angeles Daily News – which was based in the Valley – was decidedly pro-secession.

There are several things that make San Fernando Valley secession different than the 2016 presidential election. While the Valley has more Republicans than the rest of Los Angeles, it is still a majority Democratic area. Every voter is urban. The two sides had relatively similar arguments about what would happen if the Valley seceded. Valley secession leaders did minimize the potential disruptions. LA’s black neighborhoods emphasized how they would lose out financially if the Valley seceded, but there were few accusations of racism. In the end, the pro-secession movement was even more based on emotion than Donald Trump’s campaign. Trump promised to make American great again. He made incredibly vague policy promises. Trump’s promises may not be credible. But Valley secession leaders openly said they couldn’t deliver on their initial promises of divorcing LAUSD and keeping all the tax revenue.

A slight majority of San Fernando Valley voters still believed secession was a good idea and voted to leave the city! Why would they believe the promises of the secession campaign, even if all the evidence said secession wouldn’t provide tangible benefits for Valley residents?

- Disrespect: Various activists had discussed secession for decades. They felt they were not given a full share of public services, even though they paid a disproportionately high bill compared to the rest of Los Angeles. I don’t remember anyone counting what percent of potholes were unfilled in the Valley as compared to downtown. “We aren’t getting a full share” may be one of those things that is entirely symbolic and not based on rational calculation.

- If the moral claim rings true, people may turn a blind eye to empirical fact: The facts were not on Valley secession’s side. The county set the terms for secession after certifying that the Valley would be a viable independent city. The terms were not ideal for secession leaders. One balked and abandoned the campaign. The rest held on to their cause, despite mounting empirical facts about how any new city could not do what they wanted to.

- People emphasized moral claims when policy issues were murky: In 2002 the Los Angeles Unified School Board was so dysfunctional that creating a new Valley School Board with new criteria and policies seemed a lot easier than fixing LAUSD. School board governance played a major role in the 2005 mayoral race and Antonio Villaragosa’s first two years as mayor. No one really knew how to solve the giant mess. No one had a good policy idea. Voters may have been quicker to embrace the symbolic politics of secession because no one offered a policy solution to the tangible problem of underperforming schools.

Now let’s think about what we know of Trump voters:

- Disrespect: Definitely. Trump voters tend to say the federal government has forgotten them. The political class may not focus on rural areas. Remember, disrespect is a feeling that may or may not have a basis in fact. So is neglect. It’s entirely possible for multiple groups to feel disrespected by the power structure, and for those groups to hate each other.

- If the moral claim rings true, people may turn a blind eye to empirical fact: Trump offered a wide range of campaign promises, and voters didn’t seem to mind when some of these contradicted each other. In particular, Trump’s tax policies clearly favored the rich. When I think of moral claims ringing true, I think back in the first primary debate. Trump was asked if he would back the Republican nominee no matter what. He refused to say yes. Later on he attacked other Republicans for being in lobbyists’ pockets and bragged about buying influence. The moral claim was very clear: “every politician is a self-serving asshole, but I’m the only one who is honest about being an asshole.” That’s when I thought Trump had staying power.

- People emphasized moral claims when policy issues were murky: A lot of industrial workers are facing downward mobility. There’s a tendency to focus on Trump voters not being the absolute poorest, then discounting any kind of economic argument. But Trump voters are disproportionately older. Regardless of partisanship, most of the parents I have met care deeply about their children’s opportunity to have a good life. I spent my teenage years in an area that transformed drastically from farmland to suburbia. I left for college before the transformation was finished, so I’d go home and my parents were going to new malls that didn’t exist when I was growing up there. All of this was positive economic growth, but it’s still alienating. This affects how I think about declining industrial towns? Has any politician really offered a solution for declining industrial towns over the last 20-30 years? There isn’t a good plan for how to help workers whose skills are less valuable today, or the potential alienation of economic change. We got nostalgia and moralizing about trade instead of real solutions.

I can see reasons why the people who supported Trump would also be likely to buy in to fake news. I can see why people would believe the feelings contained in these stories and want to share them widely.

At this point, I think other left-leaning writers would just look down at Trump voters and stop writing. Buzzfeed’s story about fake news getting more Facebook engagement than real news feels plausible. It’s very plausible if you don’t know many Trump supporters and you’re looking for some explanation of how they got “fooled.” I retweeted the story without thinking twice. I didn’t even read the study! A friend of mine who voted for Trump posted a critique of the Buzzfeed study design over the weekend. I read the critique, then read the Buzzfeed methodology. Hate to say it, but Buzzfeed fooled me.

Here’s the short version of what Buzzfeed did wrong. They looked up the top 20 fake news stories and the top 20 real news stories. Top 20 lists are highly unequal. The #1 hit is far more popular than #2, but the gap between #2 and #3 is smaller, etc. One huge hit skews the entire set. Remember how Buzzfeed generated massive traffic by posting a dress where people disagreed on what color it was? To make things worse, fake news should have a natural advantage in this metric. If someone is creating fictional news, it is by definition a unique story. Legitimate news outlets don’t get many exclusives. Let’s say 10 people share a fake news story about a Trump-Clinton debate, 5 share the Washington Post’s lead story, 4 share their B story, and 3 more share their third story. More people shared information from the Washington Post than a fake news site, but the fake news site has the biggest single hit. In reality, the one fake news site is competing against dozens of high profile real media organizations and getting swamped in the total volume of Facebook engagement.

So why would people believe the Facebook fake news story?

- Disrespect: Yes. Democrats’ general election campaign was mainly an argument that Donald Trump doesn’t represent the characteristics we want in a leader. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote but lost the election. Disrespect for progressive values may be an understatement for how progressives feel today, particularly if they are focused on identity politics.

- If the moral claim rings true, people may turn a blind eye to empirical fact: The main people who bought in to Buzzfeed’s fake news story are Democrats who feel big media organizations didn’t do enough to clamp down on Trumpism. Remember how people bought the myth that network TV news was avoiding “issue” coverage – another study based on terrible methods. There that many sophisticated methodologists in the world. I can’t really fault people for not understanding the weird statistical distributions that biased the Buzzfeed study when they were barely mentioned in my years of graduate level statistics classes. (It’s going to take a separate full length post to explain in detail.)

- People emphasized moral claims when policy issues were murky: In this case we need to delete “policy details” and replace it with “research methodology.” It’s easy to do a simple study of media content that compares apples to oranges. It’s much harder to compile a list of potential stories or sources and then analyze how different media organizations treat them. But this is the only way to see how rare breakout hits are and how much more attention they get than any other story or source. The statistical skills needed to analyze these data sets are also extremely rare. When I gave talks at academic conferences, most of the other panelists didn’t know what a negative binomial regression was, let alone the audience. That’s why the burden is on me to explain.

We might all be vulnerable to news that is factually incorrect but feels true. I bought in to a flawed study in an area where I spent a decade becoming an expert on that methodology, because I didn’t bother to check the facts! How can we avoid falling victim to our own weaknesses?

I think the key is to look for potentially disconfirming evidence. I wrote about this at more length yesterday, but here’s the short version. As a person sitting in my apartment writing a blog, I don’t think I have the power to affect the supply of fake, misleading and manipulative political posts. Sure, I could jump up and down blaming Facebook. But here’s the good news. Each of us has tremendous power over our own demand for fake and misleading news. I know exerting this power isn’t easy. It’s tempting to just look for evidence that supports our claims. If you are a debater or a lawyer, you want to make an argument based on the evidence that is the best possible interpretation for your side. Evidence that we might be wrong stinks. Most of the time we don’t want to look for it, and we feel like fools if we actually find it. So why bother looking for evidence that would hurt our side?

In the end, it comes down to a question of whether we want to focus on our own feelings or convincing other people. If you just want to make yourself feel good, there isn’t much of a reason to look for disconfirming evidence. Just remember that someone out there is going to recognize your laziness. If you’re lucky, they’ll just want to embarrass you for buying in to a myth. If you’re unlucky, they’ll see you as a mark, willing to hand over political power in exchange for the right set of feelings. The best way we can empower ourselves is by looking for disconfirming evidence. We can keep ourselves from being fooled. We can’t rely on others to do it for us. At the same time, knowing other belief systems is normally a pre-condition for persuading other people.