Earlier today, several in house researchers at Facebook published a study in Science regarding how much users engage with links that cut against their ideological beliefs. There are already a lot of thoughtful posts on this article, since there’s a lot to chew on. The basic finding isn’t too surprising: people are less likely to “engage” with links that do not correspond to their stated political beliefs. The authors argue there is a three-step process:

- We only see links posted by friends and other pages we follow, and they are not a random group. People tend to congregate on Facebook based on their political ideology.

- Facebook’s algorithm does not place all possible stories on our “News Feed” when we log in. It favors posts shared, liked and commended on by friends. The authors do not fully disclose how the algorithm works, but they do find it cuts down on how much people see stories that cross ideological boundaries. 5% of stories were screened out for self-identified liberals, and 8% for self-identified conservatives.

- Facebook users don’t click on every link. As I’ll discuss later, Facebook users ignore the vast majority of links to political stories. After controlling for things like the position of the link (people are much more likely to click on the first link when they log in), liberals were 6% less likely to click on a link mainly shared by conservatives. conservatives were 17% less likely to click on a link mainly shared by liberals.

This process makes sense for an individual story, but it’s a troubling model for studying months’ worth of Facebook user behavior. As Christian Sandvig points out, Facebook’s algorithm is based on what users engage with. In other words, if I tend to click on all of the fantasy baseball links I see in May, I will be more likely to see fantasy baseball links that people share in June. I’ll probably see some fantasy football links too, even though I want no part of fantasy football.

Separating step 3 from step 2 is problematic, but it appears to be the authors’ main goal in interpreting their results: “We conclusively establish that on average in the context of Facebook, individual choices more than algorithms limit exposure to attitude-challenging content.” To continue with the sports reference, this is where sociologists start throwing penalty flags. The interpretation found in the scholarly journal just happens to be the same argument that Andy Mitchell, the director of news and media partnerships for Facebook, gave when facing criticism last month. (See Jay Rosen’s criticism here.) As I argued weeks ago, Facebook isn’t in a position to get the benefit of the doubt. We’ll get back to the problems of how to interpret the article’s findings in a minute. First, it is important to understand how the group that the authors claim to study and the group they actually study are very different.

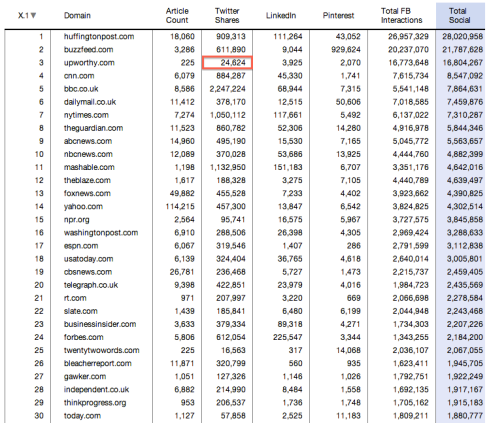

As Eszter Hargittai and other sociologists have pointed out, 91 percent of Facebook users were excluded from this study because they did not explicitly disclose their political ideology on their Facebook biography. Users were excluded for providing ideologies that weren’t explicitly liberal or conservative – a user who said their politics “are none of your damn business” would be dropped. It is unclear how self-identified “independents” were treated in this study (none of the posts I have seen mentioned this). My political scientist friends would like me to point out that self-identified independents are often treated as “moderates” when they are actually covert partisans. Users who did not log on at least four times a week were dropped as well.

Once Hargittai added all the exclusions, just under three percent of Facebook users were included in the study. As she argues, the 3% figure is far more important than the 10 million observations:

“Can publications and researchers please stop being mesmerized by large numbers and go back to taking the fundamentals of social science seriously? In related news, I recently published a paper asking “Is Bigger Always Better? Potential Biases of Big Data Derived from Social Network Sites” that I recommend to folks working through and with big data in the social sciences.”

The 3% of Facebook users who are included in the study are probably different from the 97% who are not.At this point, it would probably be helpful to separate the two groups

What Happens for People in the Sample?

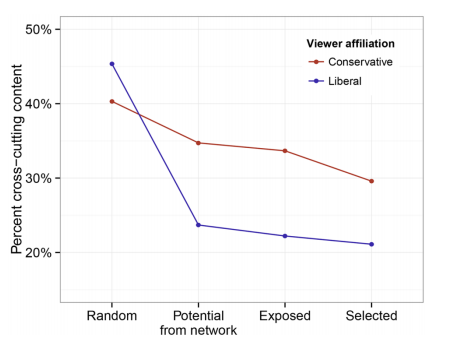

One of the hardest things for a scholar to do is publish findings that aren’t surprising. We already know that people tend to have social networks with disproportionately like-minded people. The biggest effect that the Facebook researchers found is homophily. We don’t see a random selection of stories when we log on to Facebook because our friends aren’t a random group of humans. We see stories from people who we are friends with – assuming we haven’t muted those friends because of their postings – and from pages we follow. Most media scholars have found some degree of self-selection, and found it is most prominent online. Neither the study’s authors or critics want to emphasize this point, but the results seem pretty clear in the graphic below (reproduced from the article):

Critics focus on the role of the algorithm (the “exposed” line in this graphic) versus the role of users choosing to ignore stories. When I first read the term, I thought “users’ choice” included choice of friends (the big drop for “potential from network” in the graphic). Apparently this only refers to whether users choose to click on a story or not (the last line of the graphic). It does not refer to whether users choose to unfriend or block a user because of their political beliefs. Maybe I’m thinking of this differently because I recently talked with someone who chose to unfriend everyone who didn’t share her political views. If we include adding and dropping friends to the big ledger of “user decisions” and Facebook’s friend suggestion algorithm to the big ledger of “algorithmic influence,” it is much easier to see why the authors would argue user behavior is so important, but I may be giving them more credit than they deserve.

The “News Feed” algorithm picks favorites, and we don’t fully know how, which is very troubling. On the other hand, it is only picking from the narrow subset of stories our friends have posted, and that may be a very narrow ideological range. As I wrote weeks ago, Facebook clearly has its thumb on the scale by not showing everything on a user’s “News Feed” when they log in. Facebook’s in-house researchers acknowledge some degree of algorithmic censorship of stories that are mainly shared by the other side instead of the user’s side. The effect is 5% for liberals and 8% for conservatives. This looks like Facebook has its thumb on the scale. However, the weight comes from who we are friends with.

Click-throughs as the End Measure? Really?

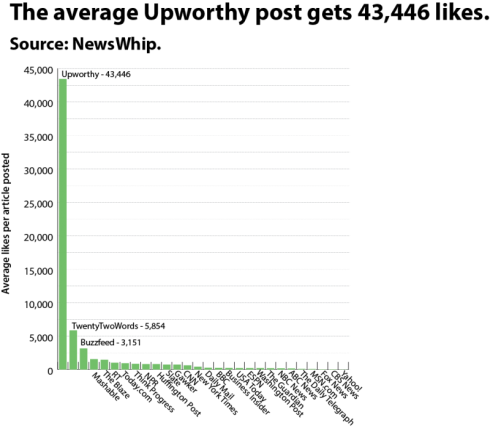

The emphasis on people clicking links was surprising to me, because “clickthroughs” are relatively rare. This study only included people who provide their political ideology on their Facebook pages. These users are likely to be more engaged with politics. We would expect them to be more likely to click on political links than other users. But the overall click-through rate reported in this article was only 6.53 percent. As many scholars and writers are finding, social media “engagement” often has a very low correlation with reading the link. In many cases, the low correlation is driven by posts that get a lot of likes and comments, even though people don’t read the story that gets linked to.

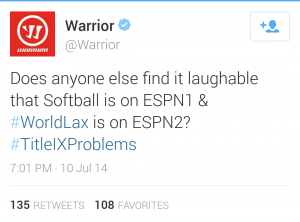

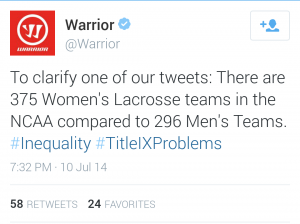

Imagine someone linked to a story about Hillary Clinton’s speech where she advocated for more pathways to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Furthermore, imagine the person sharing the story is a conservative, arguing against Clinton’s “pro-amnesty” position. Other conservatives may rally around the Facebook post, seeing it as an opportunity to voice their complaints about Clinton instead of new information to be consumed to make more informed decisions in the democratic process. This behavior happens on both sides of the aisle. Progressives may post a link about Rand Paul’s avoiding a campaign stop in Baltimore for the same reason.

What About People Excluded from the Study?

97% of Facebook users were excluded from the study. Some of these users will be just as partisan and ideological as the people who were included in the study; they just declined to put their ideology in their bio page. Other users may be less ideological or less interested in politics. Because most people interested in Facebook’s effect on the news are interested in political news, it is easy to overlook the fact that a lot of people who write online may not be all that interested in politics. (In my dissertation, I found a strong preference for bloggers publishing non-political phrases instead of political phrases during the time period of the 2008 election, but there are critical methodological differences between repeating phrases and showing holistic interest.)

If people do not engage in posting political stories or reading most political links on Facebook, would we expect them to learn anything about politics when they log on? I’m not sure if any research has been published specifically on this question yet, but studies of television “infotainment” suggest the answer is yes. Matthew Baum and Angela Jamison found that people who avoided the news but regularly watched shows like Oprah and David Letterman were better informed about politics than people who avoided the news and Oprah or Letterman. (Full disclosure, I worked as an RA for years on a project with Tim Groeling and Matt Baum.) Watching the news or reading the newspaper provides more information than “soft news,” but soft news can be surprisingly effective in communicating the broad strokes of current events.

Skimming Facebook may also give people the broad strokes of current events. People who have read their Facebook wall in the last two weeks may know there was a riot or uprising in Baltimore, even if they do not regularly watch the news or click on links to news stories. The difference in Facebook is exposure to political information is largely contingent on who your friends are, and your friends are more likely than not to congregate on the same side of the political spectrum. Thus, some people may have heard about the Baltimore riot while others heard about the Baltimore uprising.

Ironically, it is Mitchell, the Facebook executive, who offers the best advice on how to treat Facebook as a potential news source:

“We have to create a great experience for people on Facebook and give them the content they’re interested in. And like I said earlier, Facebook should be a complimentary news source.”

The problem with this is skimming Facebook could make it easy for people to feel like they are getting informed without actually being informed.